Taking Steps to Address a Preventable, Yet Increasing Threat

Only a year or two into the course of my legal career, I met a young software engineer who immigrated to the United States. Tragically, my friend lost his wife and first child immediately following child-birth. I was humbled when asked to investigate whether the deaths could have been avoided. As it turned out, it appeared unlikely a different course of medical care would have changed the outcome. I still recall feeling both disappointed and powerless that I could not ease my friend’s pain even if there was no basis to represent the interests of his deceased love ones.

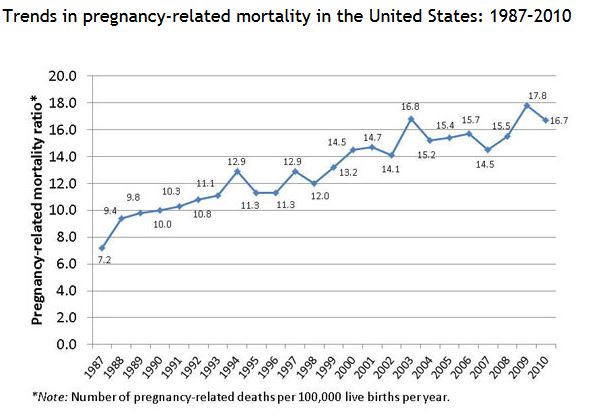

Lost in joy and anticipation, we often forget about the risks that confront both mother and child in pregnancy and childbirth. We were surprised to learn recently that in the United States, a country with one of the highest expenditures in health care per capita throughout the world, the rate of severe maternal complications and death during pregnancy have steadily increased over the last 15 years. More troubling is that the causes of maternal morbidity and death are largely preventable.

In a recent article for the Deseret News, writer Lane Anderson quotes Carolyn Miles, CEO of Save the Children, who pointed out that in the last 15 years the U.S. has slipped from 4th to 31st on the list of the best places to have a baby based on rates of maternal death during childbirth. In fact, the U.S. is one of only 8 countries to see an increase in the rates of maternal deaths since 2003 according to a study by the University of Washington. The same study identified lack of access to perinatal care, obesity and diabetes as among the most important risk factors for maternal mortality. Another risk factor, hypertension, is cited along with diabetes and obesity as increasing the risk of post-partum hemorrhage – one of the leading causes of death after childbirth.

Perhaps most alarming is the disproportionate impact on black women in urban America. As Miles put it, black woman in the U.S. have double the rate of maternal death than a woman in Iraq. CDC statistics show the disparate impact: from 2006-2009 the rate of maternal death was 11.7 per 100,000 live births for white women, 35.6 per 100,000 live births for black women, and 17.6 per 100,000 for women of other races.

The CDC also weighed in on severe maternal morbidity in the United States, a problem affecting more than 50,000 women in the U.S. each year. Data shows an incidence of maternal morbidity of just 1 in 163 deliveries in 1998-1999 steadily rose to 1 in every 74 hospital deliveries as of 2010-2011. And, between the two-year periods of 2008-2009 and 2010-2011, the incidence of severe maternal morbidity during hospital deliveries increased 26.1%. The rise in severe maternal morbidity is “likely driven by a combination of factors, including increases in maternal age, pre-pregnancy obesity, pre-existing chronic medical conditions, and cesarean delivery.”

Severe maternal morbidity has recently come to focus through a study published in the April 2014 issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology (login required). The study compiled data from 115,502 women who delivered children between 2008 and 2011. The researchers observed an incidence of severe maternal morbidity in 2.9 per 1000 births. The study identified the most prevalent forms of SMM, including postpartum hemorrhage and hypertensive complications, which together accounted for more than two-thirds of severe morbidity. In addition, several risk factors were identified along with their odds of being associated with SMM. Placenta accreta is a condition where the placenta is attached too deeply into the uterine wall and was the characteristic most strongly associated with SMM. Other factors associated with SMM were preterm delivery, antenatal anticoagulant or cigarette use, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, placental abruption, and prior cesarean delivery.

Significant maternal morbidity and death is a problem that for many women can and should be prevented. Studies show that 40-50% of all maternal deaths are preventable. Moreover, it’s estimated that 93% of hemorrhage related deaths and 60 % of hypertension related deaths were potentially preventable. Medical errors which could have prevented death from hemorrhage include the failure to pay appropriate attention to the clinical signs of hemorrhage and associated hypovolemia, failure to act decisively and provide lifesaving measures, and the failure to restore blood volume in a timely manner. See Current Commentary, The National Partnership for Maternal Safety in Obstetrics & Gynecology, May 2014.

Fortunately, the problem is not unrecognized, and change is in the works. Recent commentary in Obstetrics & Gynecology discusses how leaders from private and public health care organizations formed the National Partnership for Maternal Safety to focus on strategies to improve maternal health and safety in the United States. The partnership met in 2012 and identified the need to develop and implement three “safety bundles” to address the most common and preventable causes of maternal morbidity and mortality: hemorrhage, severe hypertension, and venous thromboembolism. A “safety bundle” is an evidence-based method of improving the processes of health care. As of 2013, the Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care supported a goal that would implement safety bundles in every birthing facility within three years.

Many of the practices that could go into a safety bundle are already recommended by the Joint Commission, the organization responsible for accreditation and certification of U.S. health care providers to certain performance standards. For example, the Joint Commission recommended the use of pneumatic compression devices to prevent the increased risk of venousthromboembolism (VTE) in women undergoing cesarean delivery. Another Joint Commission recommendation poised for adoption as a safety bundle is evaluation of postpartum patients at high-risk of VTE, such as obese patients, for anticoagulation with low-molecular weight heparin. Widespread incorporation of the use of compression devices or postpartum anticoagulation could significantly reduce the incidence of VTE and what is considered the most preventable cause of severe maternal mortality.

Everybody benefits when health care institutions not only recognize preventable harms, but implement changes to prevent those harms from occurring again. The joy of introducing a new life to the world should never be marred by serious harm or death to a mother. We appreciate the health care leaders who are helping to improve health care and install safeguards to secure the safety of all mothers and their newborn children.