A Pentagon review of the military health system released last year shows that from 2010 to 2013, the average rate of injury to babies during delivery in military hospitals was double the national average. Meanwhile, military facilities delivered nearly 49,000 babies in 2013 alone.

These statistics provide a shocking backdrop to a recent decision by the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals upholding the dismissal of a lawsuit on behalf of a severely disabled child with cerebral palsy. The statistics recited above and the decision were reported on May 28, 2015 in the Military Times. The decision in Ortiz v. United States, 2015 WL 2330230 (10th Circ.), issued on May 15, 2015, is tantamount to a declaration that a viable, full-term fetus born to a woman in active military duty has no right to compensation for permanent injury caused by medical negligence directed to the fetus. Certainly a ruling so limiting the rights of a viable fetus would be seen by certain activists as creating a slippery slope.

The decision from the federal appellate court stems from a lawsuit filed in federal district court on behalf of a baby girl born to Air Force Captain Heather Ortiz on March 19, 2009. The now six-year-old child known only as I.O. in court documents suffered permanent brain damage and severe disability from prolonged deprivation of oxygen immediately before birth.

Captain Ortiz arrived at Evans Army Community Hospital in Fort Carson, Colorado for a scheduled C-Section. Mother and unborn child were doing well until obstetrical staff administered Zantac to prevent aspiration of gastric acid during the C-Section. Unfortunately, Ortiz was allergic to Zantac. In order to counteract the allergic reaction to Zantac, care providers administered Benadryl. Benadryl had the ill-effect of lowering Ortiz’s blood pressure. As a result of the mother’s hypotension, there was decreased flow of blood to the uterus and placenta, and inadequate perfusion of oxygen to properly support the child.

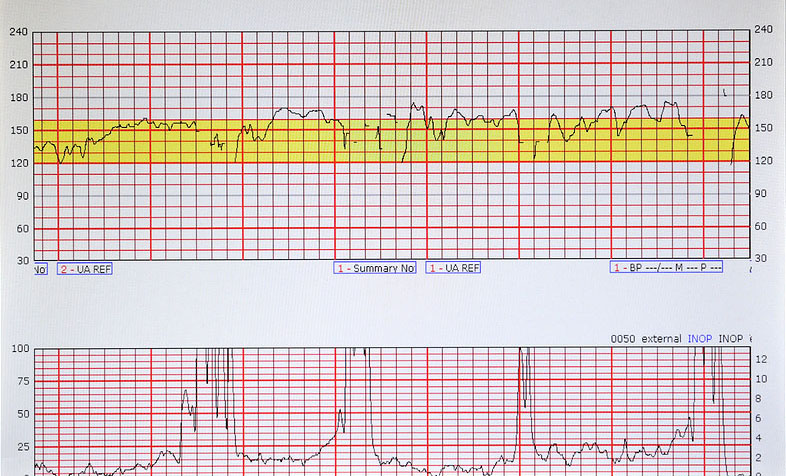

Ortiz’s hypotension and the resultant decrease in flow of oxygenated blood to I.O. would predictably result in an abnormal fetal heart rate pattern visible upon inspection of the fetal heart monitor strips. Not surprisingly, the lawsuit alleged I.O’s injuries were caused by the failure of hospital staff to timely review the fetal heart monitor strips, recognize a fetal heart rate pattern consistent with distress, and prevent injury to the child.

In dismissing the case, the district court and then the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals relied on an exception to the Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA) called the Feres Doctrine. Also known as the “incident-to-service” test, the doctrine stems from a landmark 1950 Supreme Court decision in Feres v. United States, 340 U.S. 135 (1950) and focuses on whether the plaintiff’s injuries arise out of or occurred during the course of an activity incident to military service.

Importantly, the Court of Appeals rejected a line of cases from other federal courts which found an in utero injury to a fetus independent and unrelated from any injury to a mother. Instead the Court defined the test in Ortiz as “whether the civilian (fetal) injury had its genesis in a service-related injury to a service person(mother).”

While recognizing the facts in this case “exemplify the overbreadth (and unfairness)” of the Feres Doctrine, the Tenth Circuit nonetheless found I.O.’s injuries were incident to her mother’s drop in blood pressure and therefore “incident to the mother’s military service”. Thus, even though Captain Ortiz suffered no long term consequence as a result of the drop in her blood pressure, the Court determined Ortiz’s hypotension was the source of the injury to the child and therefore the basis for applying government immunity to the Army Hospital.

The Ortiz Court’s opinion is certainly thorough. Nonetheless, the conclusion I.O.’s injuries were derivative of her mother’s blood pressure problems was poorly thought out. The Tenth Circuit’s conclusion “[w]ith respect to the alleged failure to scrutinize the fetal monitoring strips, there is no independent injury to support this claim” is inconsistent with the medical basis of the claim. The Court of Appeal’s either ignored or failed to recognize that the hospital’s failure to monitor the fetal heart rate strips was the cause of a separate and distinct injury. Instead, the Court demonstrated a distorted application of the law to the facts when it agreed with the district court that “but for” the administration of the Zantac and Benadryl and resultant blood pressure problems, the failure to review the fetal heart monitoring strips would not have caused I.O. injury.

Ironically, as pointed out in the Military Times article, the Ortiz’s case could have proceeded to resolution if the I.O.’s father was the active duty member of the military as opposed to Captain Ortiz. But, perhaps more concerning is the Court’s failure to realize that the drop in the mother’s blood pressure was merely the catalyst which caused the reduction in the flow of oxygenated blood to the fetus and the start of fetal distress. Certain measures should be taken once fetal distress is recognized to relieve the underlying problem. In this case, had the hospital staff recognized the child was in fetal distress, delivery may have been indicated on an emergent basis.

I.O’s injury was incident to the failure to monitor the fetal heart strips and respond to the distress of the fetus. Even concluding as the Court of Appeals did that Captain Ortiz suffered an injury, I.O.’s injury was not derivative of her mother’s injury in the sense of how a widow’s wrongful death claim is derivative of their spouse’s death, or any sense for that matter. As alleged, had the hospital staff reviewed the fetal heart monitor strips, I.O. could have escaped injury. For the Court to ignore the true nature of the negligence and I.O’s injury, then go out of its way to dismiss the case is, in our opinion, an injustice.